(Thursday, 24 May 2018)

By Micha-Rose Emmett, CS Global Partners

The appetite to achieve a second citizenship grows year-on-year. It’s an exciting time to be in an industry shifting and expanding to meet the needs of the market. But with an increased number of countries and clients poised to enter the investor immigration scene, a great responsibility comes with it to ensure that frameworks remain robust and attuned to side-step those looking to breach the system.

Earlier this year, the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development), a forum to promote sound economic policies worldwide, released a consultation document entitled Preventing Abuse of Residence by Investment Schemes to Circumvent the CRS*, relating to the suspected misuse of residency by investment (RBI) and citizenship by investment (CBI) programmes as a means of tax avoidance. The OECD invited stakeholders from the industry to comment and share their views to find mechanisms to mitigate potential abuse.

The consultation document, derived from suspicions that the investor immigration industry was being used by those wishing to circumvent the system, raises two very important elements of consideration in the context of an expanding environment: how we define the products offered and future regulatory demands. Though the title of the report directs the OECD’s response initially and predominantly at residency by investment schemes, there were numerous occasions where the consultation document defined citizenship by investment under the same banner, which presents a problem in rectifying the suspected transgression. A number of key factors separate CBI and RBI within the broader investor immigration scene:

- Direct citizenship by investment programmes offer citizenship only. Programmes such as Dominica and St Kitts and Nevis do not provide a residency status, and no certificate of tax residence is issued to economic citizens upon receipt of citizenship.

- Persons cannot falsely claim to be a tax resident because the citizenship alone cannot determine an individual’s residency status.

- Direct CBI programmes provide only a certificate of naturalisation. Any application to request a passport, or other official documentation related to identity, occurs after the respective government department (i.e. the citizenship by investment unit) grants the citizenship.

- An economic citizen’s place of birth is declared on their new passport. There is no attempt to conceal any information – thereby minimising the risk in aiding or abetting nefarious characters who intend to commit tax evasion or identity fraud.

- Residency by investment programmes may provide certificates of residency or ID cards even if a resident does not actually have a physical presence in the jurisdiction where the residency has been granted.

Transparency and education can play a positive role in the OECD ratifying this issue. Separating CBI and RBI allows regulations to be implemented fairly and consistently to meet the demands of this developing industry. Due diligence from all stakeholders is paramount, not just when it comes to granting citizenship or residency, but in the execution of CRS policies as well.

This is just one example of how the industry will be implicated as it grows and evolves. It invites the question, what future considerations may we have in this growing industry? Technology is certainly one important consideration. At the time of writing, reports of a new cryptocurrency ‘citizenship coin’ had been announced, which unlocks a new set of complications for the industry. While innovation in the industry should certainly be applauded, regulatory frameworks must be considered in light of its rapid growth. How will a ‘citizenship coin’ adhere to the strict anti-money laundering policies governing these CBI programmes? And what role will CRS play in respect of the reporting requirements of clients who decide to use cryptocurrency?

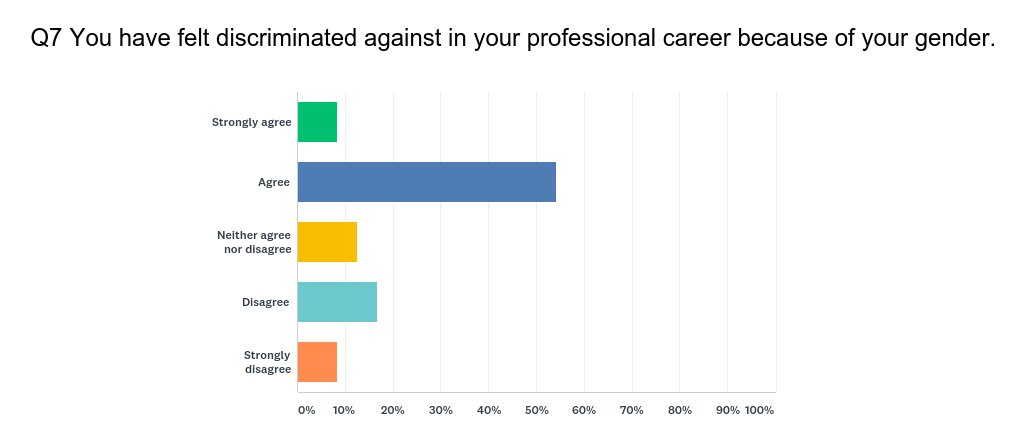

These issues arising from the industry’s evolution call into question broader periphery topics relevant to any growth sector. Among them is diversity of representation. Contextually, the investor immigration scene sits within the broader financial sector, which has recently been subject to some criticism regarding gender equality. A look at the gender pay gap in the United Kingdom financial services sector revealed that on average, men are paid 24% more than women. The disparity in equality was made evident when 10,000 of the nation’s largest firms were called to submit pay gap information to the UK’s Office for National Statistics. This is just one of many disproportionate statistics that demonstrate the timeliness of addressing gender equality in the investor immigration sector. Indeed, lifestyle magazine of the industry, Belong, launched a survey** inviting comment from the industry.

As countries look to adopt immigration programmes to stimulate their economies, so too will clients follow. And, this will only increase the appetite for professionals to become engaged. The industry is poised for new and innovative developments, and we must look to best practice within the industry, and that of the broader financial sector, to ensure frameworks are robust enough to cope with the increased demand.

*The Common Reporting Standard (CRS) is a system of information exchange between nations, enabling financial institutions such as banks to automatically share details of users to combat tax evasion. CRS is part of the OECD’s framework, and was first approved for execution on request from the G20 Summit in 2014.

**It can still be completed via the link https://www.surveymonkey.co.uk/r/womensurveybelong